Regular Expressions; Or, How To Create Your Own Language

This post situates regular expressions or “regex” within the computer science context of regular grammar and finite automata.

Regexes: formulae for search patterns

What is a regular expression? “A regular expression is an algebraic formula whose value is a pattern consisting of a set of strings, called the language of the expression” (Randall Nelson, “Regular Expressions”).

We can for instance say that the regular expression a, consisting of a set of strings X such that X = 'a', matches the character a. Similarly, the regular expression abra matches the characters abracadabra. The reverse is not the case: the regular expression abracadabra does not match the characters abra.

“Regexes” are thus instances of regular grammar in action, “formulae [plural] for search patterns” being equivalent to “regular grammar.” By “grammar” I just oversimplifyingly mean the entirety of a formal language’s “rules of the game” pared down to a relative few productions.

The grammar/compiler analogy

This notion of grammar is analogous to the notion of compilation in computing. And as we’ll see, different types of grammar are analogous to different steps in the code compilation process.

The compilation process in brief

Let’s begin with an expression: x = a + b * c.

The first step in compiling this expression down to something an assembler can understand involves lexical analysis. Lexical analysis transforms a stream of lexemes or atomic language units into a stream of tokens. Accordingly another name for lexical analysis or lexing is “tokenization.” We now have something like id = id + id * id.

The second step in compiling down our original expression entails syntactic analysis. Here we deconstruct our token stream down to a parse tree. Our token stream above yields the following:

Statement

/ \

id = Expression

/ \

Expression + Term

| / \

Term Term * Factor

| | |

Factor Factor id

| |

id id

Thirdly, we perform semantic analysis to go from the above parse tree to a semantically verified–i.e., meaningful–parse tree.

Finally, we are able to generate what’s known as “intermediate code”–something like the following:

t1 = b * c

t2 = a + t1

x = t2

This intermediate code can be optimized in various ways, depending on the platform we are utilizing for compilation. This optimized code gets turned into “target code”: at last, code an assembler can understand.

For more info on the compliation process described above, I recommend Ravindrababu Ravula’s Compiler Design YouTube series.

The compiler/grammar analogy: the Chomsky Hierarchy

Back to grammar, recalling that regular expressions implement regular grammar, and that grammar can be summed up as the entirety of a formal language’s theorems or rules pared down to a relative few axioms. How does regular grammar in particular fit into grammar in general?

The convention computer scientists have adopted to contextualize regular grammar makes use of the theoretical “hierarchy” of grammars developed by linguist Noam Chomsky. According to Chomsky, there are actually four types of grammar: unrestricted, context-sensitive, context-free, and regular. These four types of grammar are analogous to the stages of the compilation process outlined in the previous section. Unrestricted grammar is to code as context-sensitive grammar is to a semantic analyzer, as context-free grammar is to a syntactic analyzer, as regular grammar is to a lexical analyzer. Regular grammar is the most restrictive form of grammar, just as a lexer performs that most narrow function in the compilation process of turning an expression into a stream of nothing but tokens.

Regexes: food for finite automata

While search pattern formulae make use of regular grammar, a single formula for a search pattern is called a regular language. In turn, regular grammar–implementable in a regular expression language–performs lexical analysis via use of a “finite automaton.” Put another way, regexes are regular languages that can perform lexical analysis via use of finite automata. It can also be said that “a regular language can be accepted by a finite automaton” (Bill Byrne, “Chomsky Hierarchy for Languages”).

What’s a finite automaton?

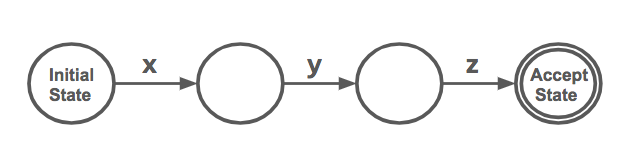

A finite automaton is both a graph and a type of finite state machine. A finite state machine, in turn, refers to a collection of states with transitions between them. For instance, a finite state machine that only accepts the string xyz can be graphed in the following way:

Consider a “finite automaton” or “finite state machine” to be a graph with

- a finite number of nodes (for regular expressions these are boolean states),

- a single “start” or “entry” node (the “Initial State” in the above graph), and

- edges that are the “rules” comprising the regular language being fed into the finite automaton.

What’s a finite automaton with regard to regexes?

In addition to the above three criteria, a regular expression graph contains a final “end” or “exit” node (the “Accept State” in the above graph).

All nodes in our graph implicitly contain values. The “Accept State” node contains a truthy value; all other nodes contain falsey values.

The finite automaton decision procedure for regexes is thus to

- start at the “start” state,

- read in characters from input and see which rules are met (i.e., traverse the graph), and

- when you’ve read in all characters from input, check which node you’re at and return its value.

Going from a finite state machine to a regular expression and vice versa

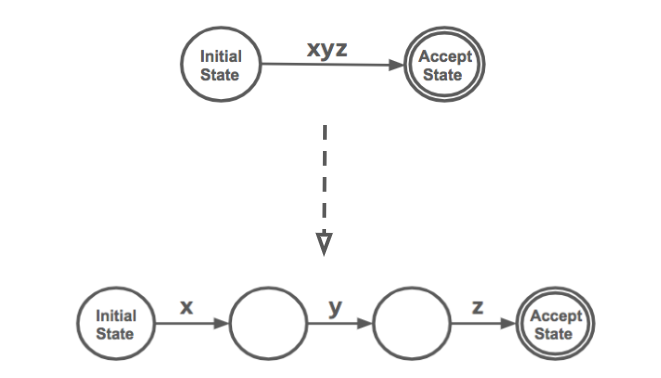

There exists a direct relation between finite state machines and regular expressions. Going from a regular expression to a finite state machine is a matter of “expanding” the single-edge graph of the former into a graph with many edges.

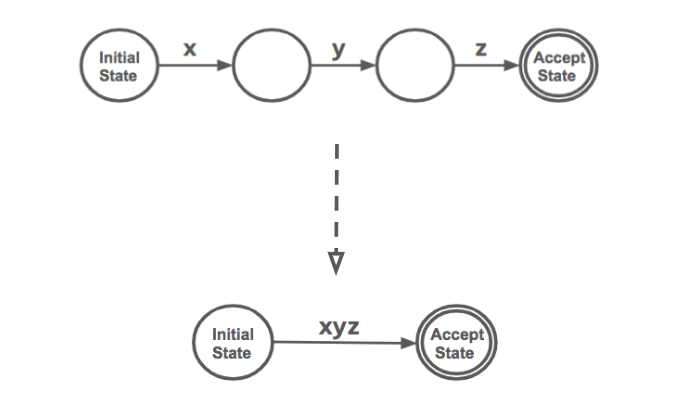

Conversely, going from a finite state machine to a regular expression is a matter of “compressing” the many-edged graph of the former into a graph with a single edge, comprised of all the characters making up the regular expression.

As finite automata are to pattern recognition, regular expressions are to pattern generation. “Just as finite automata are used to recognize patterns of strings, regular expressions are used to generate patterns of strings” (Nelson, “Regular Expressions”). Regular expressions yield patterns. Given input, such a pattern yields a decision procedure. Such a decision procedure yields a boolean result.